Mykki Blanco couldn’t find a place to hide their HIV medications. Having just wrapped a tour, the performance artist turned experimental rapper, who uses they/them pronouns, was hosting an after-party in a hotel suite at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles.

When Blanco heard friends’ voices from the hallway, they panicked, scurrying to find a safe place to stash the meds. After all, this was not home, where this was standard practice. Here, there were fewer trusted hiding spots. Blanco fretfully tucked the meds under the mattress, desperate to conceal their status. Later, as partygoers filed out, Blanco slipped into another depressive state.

“I felt so bad about myself, and I said, ‘Enough of this,’” they recall to POZ.

That night, Blanco took to social media to disclose their HIV-positive status, noting that they’d been diagnosed in 2011 and they were healthy. “Fuck stigma and hiding in the dark, this is my real life,” Blanco wrote on Facebook in 2015, adding at the time, “I’ve toured the world three times, but I’ve been living in the dark. It’s time to actually be as punk as I say I am.”

***

Born Michael Quattlebaum Jr. in Orange County, California, and raised in North Carolina, Blanco was already used to living brazenly—sometimes in bras, sometimes in caramel-hued wigs.

Their androgyny was a thrilling, uncharted leap forward for the LGBT community, as hip-hop had never quite experienced a queer, Black, rapping Jew whose knee-high combat boots were firmly pushing into a genre mold steeped in macho posturing. No wonder the Village Voice once called Blanco a “gender ninja.”

But despite their savageness onstage, it would take them four years after the 2011 release of their acclaimed collection of poetry, From the Silence of Duchamp to the Noise of Boys, to live openly as a person with HIV.

Blanco’s mom knew. A few friends knew. But Blanco, who says “there were no positive examples of anyone doing what I did and continuing to thrive,” still feared that telling anyone beyond the closest of allies would kill their music career.

They couldn’t envision a world where a rapper who happened to be queer, happened to present as femme and happened to be HIV positive could succeed, so Blanco thought they’d step back from producing quick-fire rhymes, maybe become an investigative journalist.

The alternative—becoming America’s “HIV rapper”—seemed daunting and limiting.

“In the very beginning, standing up for HIV awareness and stigma, to me, felt too much like a badge and a weight, where all of a sudden, all of my art, all of my music, all of my work that has so much to do with how I navigate the world would’ve just been labeled through this vehicle of like, ‘Oh, this is the HIV artist,’” Blanco says.

But they kept writing. In 2016, having released three EPs and three mixtapes over the years, Blanco debuted their first full-length album. With Mykki, they were keen on keeping the conversation focused on the music—not sexuality, not race, not HIV.

Of other artists, Blanco says, “they’re not called ‘straight musicians,’” citing examples such as Grimes and Solange. “I’m an artist. To call me anything else takes us back to a place that we need to be far ahead of,” which is “the Jim Crow days.”

Still, when Blanco began to receive despondent direct messages via social media from fans living with HIV, they began offering “love and light.” Blanco responds to the DMs by sharing that accepting an HIV-positive status is a personal journey that can be aided by local support networks. Blanco reminds those seeking guidance that their harrowing story is proof that a dark path isn’t dark forever. “I’ve grown,” Blanco often writes back.

“Overall, people have told me, ‘Just seeing you continue to work, continue to achieve things, continue to not stop’—I guess…” Blanco stops before backpedaling. “Why am I saying ‘I guess’? I know that’s inspiring. I know I didn’t have a me to look to. I think that, especially if you’re a person of color, yes, it matters.”

Full-length album cover

Images from the “Loner” (left) and “High School Never Ends” music videos

In September 2019, Blanco spoke openly in a public setting for the first time about the impact of HIV on their art. The occasion was a master lecture they gave at the United States Conference on AIDS (USCA).

Globally, Blanco had given many lectures at universities on their performance art, but the content of this talk—“far too personal to be posted on social media” and never before addressed in any interview—focused on the traumatic aftermath Blanco experienced after being sexually abused as a child, which they believe led to self-esteem issues in their teens and early 20s.

Telling their deeply personal story in front of HIV activists at USCA, Blanco managed to hold back tears while revisiting their pain-ful past—but only because they’d already shed so many in the days leading up to it.

Before the lecture, Blanco rented a quiet Airbnb for just over a week in a “very German neighborhood” in Berlin, where they remained sequestered at a desk every day and wrote—for the first time in their life—an account of the sequence of events that led to compulsive sexual behavior and, Blanco says, “contributed to high-risk behavior and how I contracted HIV.”

Blanco wrote about realizing that at age 6, they’d been sexually abused—an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show featuring sex crime survivors had jogged their memory—and that one Saturday morning after cartoons, they’d told their mother about the abuse.

Blanco also wrote about meeting older men via chat rooms and at cruising areas as a pubescent teenager. Confronting their past in such a focused, detailed and cleansing manner and realizing that soon they’d be sharing that with a room full of strangers, “I broke down sobbing multiple times,” Blanco recalls.

While writing the lecture, they leaned on their mom and the man who was Blanco’s romantic partner at the time, both of whom helped tremendously. By the time Blanco spoke at USCA, “I was confident in a way that I was able to deliver and really, I feel, eloquently talk about very touchy things.”

After three years together, Blanco and their partner broke up. But Blanco says they were left with an enlightened state of mind, having learned self-love and self-respect because “the way in which he loved me enabled me to realize that I should treat myself better.

Mykki BlancoAndré Miguel, AKA Lisboeta Italiano

These days, Blanco isn’t hiding from what they were afraid of becoming, which was an “HIV poster child.” On social media, Blanco posted a photo of their HIV meds to let their followers know “this is what I take every day, this is what keeps me untransmittable.” (Blanco is referring to the fact that having undetectable HIV means that you cannot transmit the virus sexually, a fact commonly known as U=U.)

By communicating about their day-to-day life, Blanco has realized the impact that sharing their story can have on people in the throes of a similar struggle—especially considering that “for so many people, I am actually the only person they know with HIV.”

In 2017, Blanco was one of five people featured in Epic Voices, an online series created by amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, an opportunity Blanco cherished. The videos spotlight “influential members of the LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS community” who share their stories as people living with HIV to “reenergize the response to HIV among millennial and LGBT communities.”

“I’ve realized these past few years the power that I can have,” Blanco says, attributing their newfound comfort as an HIV activist to a spiritual evolution and a new commitment to a sobriety program. Blanco writes about HIV, thinks about HIV and talks about HIV. It’s all been very cathartic.

In fact, Blanco even acknowledged that interviews such as this one help them come to terms with unprocessed aspects of contracting HIV because “you get into a habit and you take your medication every day; it’s like, How much am I really thinking about being HIV positive every day?

“I’m being forced to articulate things that have always remained so tied to my subconscious,” Blanco adds. “It just feels like a triumph to be able to be this transparent.”

In that spirit, Blanco disclosed in November 2019 on Instagram that they started transgender hormone therapy. “I’m not gay,” Blanco wrote, “I’m trans.”

Instagram post by Mykki Blanco

When POZ spoke with Blanco in October, they had just arrived in Lisbon and were back to their “healthy Portuguese life” after working in London for two weeks.

Blanco admits they were never one of those kids who always aspired to be a performer. It wasn’t even until Blanco was 25 that they became a songwriter, releasing their first EP, Mykki Blanco & the Mutant Angels, in 2012.

“The idea that I was going to be a musician creating albums, that was just not my pedigree,” Blanco says. Aware that they’re “not the most famous,” they say, “I was not someone who thought I was going to be famous” at all.

Interested primarily in being a public intellectual in their youth, Blanco emerged at a time when being a visibly queer artist was “not cool.”

Blanco came to the fore through the fringes of the underground performance-art world, thanks to booking opening spots on tours for artists such as Icelandic singer Björk, Jamaican-American electronic dance music trio Major Lazer, and the U.S. band Death Grips. Collaborations with Kanye West and British singer-songwriter FKA twigs followed.

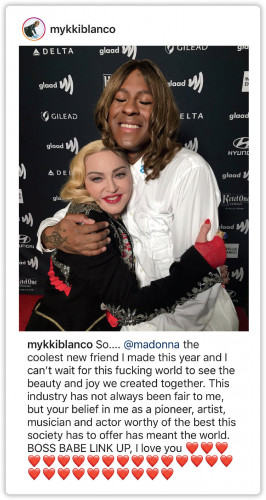

Then came Madonna. For the legend’s religious-themed “Dark Ballet” music video, released in 2019, Blanco appeared as Joan of Arc, the heroine who was persecuted and burned at the stake. Blanco’s role was a modern-day take on fearlessness in the face of condemnation for being who you are.

“She feared nothing,” Madonna said of Joan of Arc in a statement around the video’s release. “I admire that.”

The video ends with a quote from Blanco, a rousing declaration of self: “I have walked this earth, Black, Queer and HIV positive, but no transgression against me has been as powerful as the hope I hold within.”

“I’m not going to pretend the Madonna moment wasn’t a big deal to me,” Blanco says, quick not to call the collaboration a breakout moment since they’d already worked with Björk and West.

But working with Madonna “was a big deal,” Blanco says. “If anything, it was this public validation of: Yes, I have been making good work, I have a fan base that has acknowledged it, and thank you, Madonna, for lifting me up to allow more people to continue to follow me and the work I continue to do in the future.”

Blanco describes this forthcoming professional era as “the beginning of the ‘celebrification’ of my career.”

Instagram post by Mykki Blanco

The mantra in the title of Blanco’s second full-length album, Stay Close to Music, Stay Close to God, due out this year, is the very same one they leaned on when facing recent adversity.

“What has kept me most sane, what has been my rock and my spiritual foundation in the times in my life where I felt unbalanced, ungrounded, unfocused, literally that phrase—‘stay close to music, stay close to God’—was the grounding force in my life continually.”

While Blanco also plans a more dance-oriented, piecemeal mixtape, they see this album, an evolution into “uncharted territory,” as a cohesive body of work that explores the broad spectrum of their multifaceted identity. Blanco’s musicianship is evident in the album’s keen focus on composition, while their individuality shines through in its poetic self-reflection.

Blanco says their followers often don’t understand why they’re not a major star yet, why it’s been such a slow and steady climb. “Sometimes people who are pioneers, it takes them a bit longer to get to the top,” Blanco says.

To illustrate their journey, Blanco recites to POZ the lyrics of a new song called “Carry On” from Stay Close to Music: “Black and gay, I wonder if they’ll ever claim us / HIV, I have HIV, can I still be famous? / Will they wait till I’m dead to give me credit? / These thoughts run through my head / I try and dead them / And just bless God instead.”

Through navigating trauma and “taking responsibility for the times in my life that I fucked up,” Blanco has gone to dark, painful depths. In the process, they’ve found a “spiritual dimension of myself that no psychologist, no psychiatrist could’ve ever helped me discover.”

The top could be just around the corner, but right now, at this very moment, Blanco seems content just knowing that, in music and in life, they are finally being every bit as punk as they set out to be.

1 Comment

1 Comment